Credit: Shakeitupcreative.Com

When we hear the word “creativity” we tend to associate it with something artistic. At a push, we might think of companies like Apple that routinely come up with something so innovative or game-changing that they effectively reconfigure the playing field. But creativity is common to every successful firm or organisation. It is the dynamic that enables us to devise new ideas – new ideas to sell, or to make our processes more efficient. The trick is harnessing it.

Back in 1988, Teresa Amabile, now a professor and director of research at Harvard Business School, published a paper that changed the way we think about creativity. She identified three critical dimensions or levers that drive creative thinking, processes and outcomes. These are: domain expertise or technical ability; the capacity to think divergently and try new approaches or ideas; and motivation – feeling intrinsically driven to approach a task or solve a problem.

In today’s globalised and hyperconnected business context, does this model, which was conceived in the US, hold true for different countries and cultures?

A great deal of past research has explored multicultural creativity. Much of it looks at differences between small samples of countries – maybe two or three – with a focus on how different countries define creativity.

We were interested in looking at something bigger. Together with colleagues from HEC Paris and the Singapore Institute of Management, we wanted to understand what stimulates creativity on a global scale.

Pulling different levers

Just because two countries look similar, does it follow that the creative dynamics will be the same in both? Will pulling certain levers have the same result in Canada, say, as in the US?

To investigate this we pulled together all the existing research we could find on creativity in organisations – 70 years’ worth of studies covering insights into creative practices and outcomes across a total of 40 countries.

Using meta-analytical statistical tools we were able to ascertain the real effect of each component of Amabile’s model to see whether the three-lever concept still holds water. We find that it does. And not only that: looking at all of the countries in our sample, we find that the three levers (technical skills, divergent thinking and motivation) are relevant to them all. But when you compare each country, different findings emerge.

Amabile’s levers matter for every country – but how you should pull them in each one is a whole different ball game.

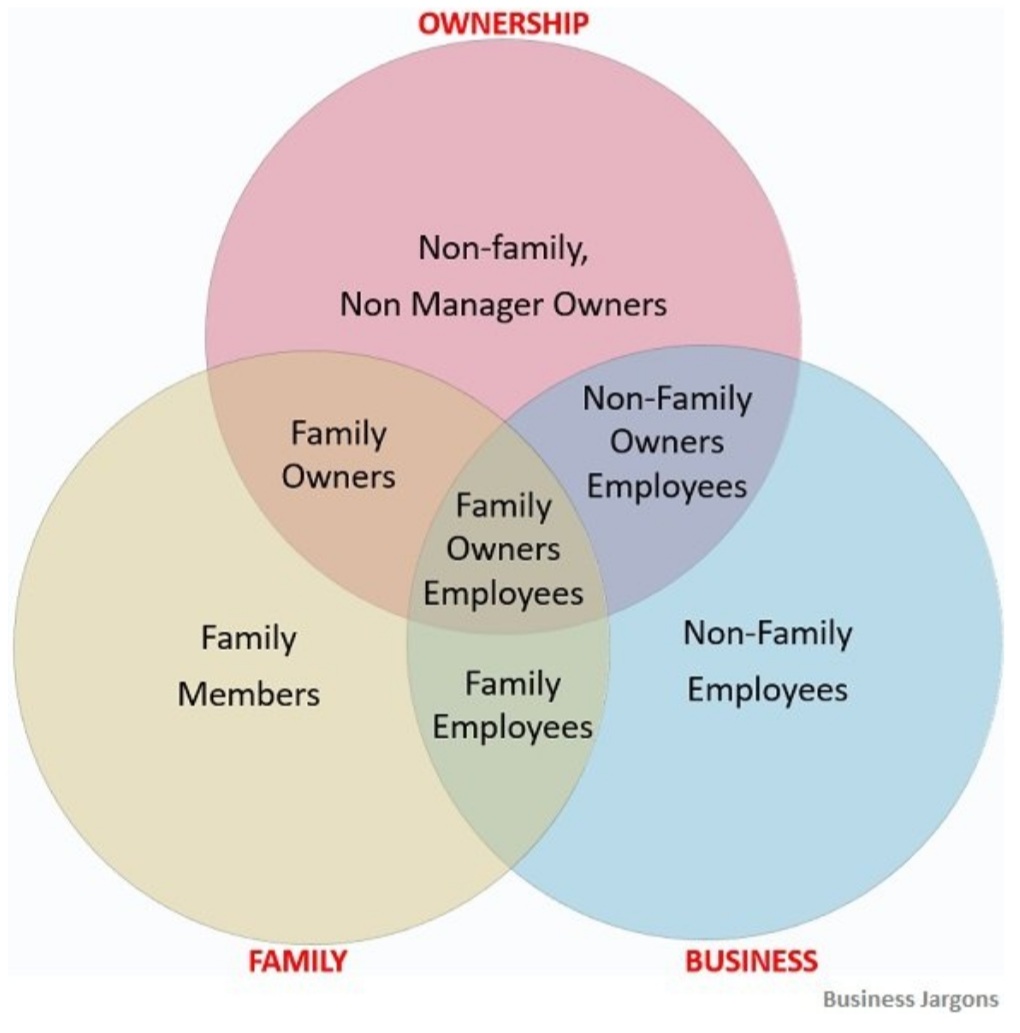

The amabile model: the three levers that drive creativity

Domain-relevant skills: These include the knowledge, expertise, technical skills, intelligence and talent in the particular domain where the problem-solver is working, such as product design or electrical engineering. These skills comprise the raw materials on which the individual can draw throughout the creative process – the elements that can combine to create possible responses, and the expertise which the individual will use to judge the viability of those responses.

Creativity-relevant skills: These include a cognitive style and personality characteristics that are conducive to independence, risk-taking and being open to new perspectives on problems, as well as a disciplined work style and skills in generating ideas. These cognitive processes include the ability to use wide, flexible categories for synthesising information and the ability to break out of perceptual and performance “scripts”. The personality processes include self-discipline and a tolerance of ambiguity.

Task motivation: This is the motivation to undertake a task or solve a problem because it is interesting, involving, personally challenging or satisfying; rather than undertaking it out of the extrinsic motivation arising from expected rewards, surveillance, competition, evaluation or requirements to do something in a certain way. A central tenet of the componential theory is the intrinsic motivation principle of creativity: people are most creative when they feel motivated primarily by the interest, enjoyment, satisfaction and challenge of the work itself – and not by extrinsic motivators.

Creativity and the cultural bundle

When Walt Disney subsidiary Pixar opened a studio in Vancouver, the idea was to produce a range of short films that would leverage the company’s popular and successful feature-film characters. But things didn’t go to plan. Within three years, the Canadian studio had closed down, leaving more than 100 film-makers out of work. So what went wrong?

On the surface, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the US and neighbouring Canada are culturally very similar. However, there are nuanced differences between them that have a profound effect on the ways that creativity is best stimulated and nurtured in each.

Our research shows that it’s the set of all the cultural dimensions of a country that determine which lever – expertise, divergent thinking or passion – will have the strongest or weakest impact in driving creativity there.

Let’s break that down a bit. Typically, there is a bundle or set of core cultural values that define a country. These are:

Individualism vs collectivism: whether people work better individually or in teams.

Power distance: how much we accept or are governed by power hierarchies.

So-called masculine-versus-feminine dimensions: very antiquated terms that denote, for example, how work-life balance and competitiveness are prioritised by the culture.

Uncertainty avoidance: how comfortable we are in dealing with uncertainty and risk.

‘When you consider the whole bundle of cultural dimensions for France and the US, you see that they are as different as France and China.’

There’s another key cultural dimension here, known as “cultural tightness”. This is not values, but the extent to which values are enforced – the degree to which individuals are expected to conform to societal norms (or not). When we dug into the data, we found that the bundle of these core defining cultural values and the degree of cultural tightness or societal conformism inherent in a country play a very significant role in determining how creativity is best stimulated there. When you look at countries through the lens of these bundles, the findings are surprising. Take two classically western countries, the US and France, for instance. Both are individualistic as opposed to collectivist societies.

At first blush, you might expect the dynamics of creativity to be similar. But, as Disney discovered to its cost when it opened Disneyland Paris, culturally the two countries are quite diverse – so unlocking creativity in each requires different approaches.

When you consider the whole bundle of cultural dimensions for France and the US, you see that they are as different as France and China. Little wonder that Disneyland Paris ran into so many problems. From the “smile” policy that didn’t go down well with French trade unions to longer-than-anticipated time spent queuing for attractions (pre-Covid, French norms involved people grouping closer together than in the US), the issues started to pile up.

Critically, because of the significant differences in their cultural bundles, the US parent company was unsuccessful at unlocking the kind of creativity in its French subsidiary that would have helped Disneyland Paris overcome its difficulties.

We also find that cultural tightness has a key effect on how the drivers of creativity work. In tight or more socially compliant cultures such as Japan, the most effective levers you can pull to unlock creativity are those that are promoted and enforced by local cultural values. However, the opposite is true in other more permissive countries such as the UK. Here, the most effective levers are those components that are not emphasised or that are even actively discouraged by local cultural values – being different pays off.

This makes sense because of the “rule” dynamic at play. If expertise development is the best lever for creativity in Japan, building skills will have a much stronger effect than other paths because, in a sense, that’s the rule or the norm. In the UK, on the other hand, where the rule book is less strictly enforced, your creativity levers will also be a bit looser. In the UK there’s a competitive advantage in being different. So it’s in your interest, creatively, to do what the culture is telling you not to do.

Now, this is all very interesting and relevant from a research perspective. But are there concrete insights and takeaways for managers – especially those managing multicultural operations?

Steps to driving creativity wherever you are

A good starting point is to understand this simple fact: the world is more different than you think. There is no global blueprint for creativity. Stimulating creativity in Italy is not the same as in France. The same goes for Canada and the US, Japan and China.

Good managers will therefore avoid making assumptions based on stereotypes or an obvious cultural difference between countries, such as individualism vs collectivism. It’s the entire cultural bundle – the configuration of all the cultural dimensions – that matters. Following these four steps can help you make better decisions about how to unlock creativity wherever you are:

1 Determine how tight or loose the culture is. Is this a strict and compliant society, or more relaxed and permissive? This helps you determine how strong the effects of each lever will be.

2 Map this culture in every dimension we discuss, not just collectivism vs individualism. Explore how power hierarchies work, the extent to which traits such as competitiveness dominate, and how comfortable people are with risk and uncertainty. Understanding the cultural bundle of a country will give you insight into what’s going to work as a creativity lever.

3 Map your own country. If you are responsible for a different market, you need to be able to see the differences clearly. And there will be differences.

4 Experiment. Look at which levers work best. Is it domain-relevant skills or expertise and knowledge? Is it ok to be exploratory and look for new things and new ways of doing things? And is it important how motivated your people feel to do the job? Track what works.

The moderating effect of cultural bundles on creativity: some examples

We were able to uncover some interesting findings in our research.

The US and Canada In the US, we found that two levers worked better in unlocking creativity: encouraging divergent thinking and building motivation. Focusing on technical skills and expertise wasn’t as effective. Conversely, in neighbouring Canada, fostering strong skills and expertise worked well.

Spain and Italy While apparently quite similar in culture, we find that building up skills and expertise works well in Italy; whereas in Spain the number-one lever was encouraging motivation and passion.

France and the Netherlands In France, like Italy, developing strong technical expertise predicts strong results. But just a few hours to the North, in the Netherlands, the best way to drive creativity is to empower experimentation and divergent thinking.

None of this means that all three levers are not important in every country. It’s simply the case that emphasising one approach over another will have more or less effective results. There are different paths to creativity and they differ across countries. Knowing this will arm you as a manager to think more scientifically about how you foster and harness creative thinking and processes.

We’ve done some of the legwork in our research, using in-depth statistical analysis. Managers can adopt a similar approach – or, alternatively, reverse-engineer the process: how does this country or region emphasise the acquisition of knowledge? Does it prioritise experimentation? Do people respond better when they are motivated? How permissive or strict is this society? This will help you draw robust conclusions concerning which path or strategy to focus on to drive creativity, wherever you are.

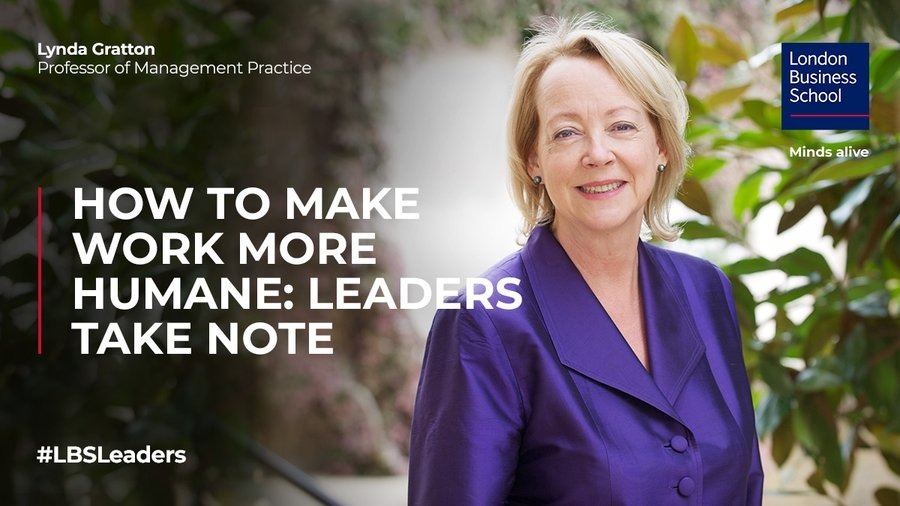

Pier Vittorio Mannucci is Assistant Professor of Organisational Behaviour at London Business School. He teaches on our MBA programme.

Credit: London Business School

What is your thought about this story?

Kindly like and share.