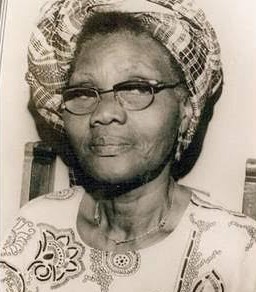

Olufunmilayo Ransome-Kuti

Olufunmilayo Ransome-Kuti was born in 1900 in Abeokuta, Nigeria, to a seamstress and a small planter whose father had been an emancipated, baptized slave returnee from Sierra Leone. She was the first female to ever attend Abeokuta Grammar School, Abeokuta, before attending a finishing school for girls in England from 1919 to 1923, where she learned elocution, music, dressmaking, French, and various domestic skills. Based on her exposure to racism in England and socialist ideals, she dropped her English names of Abigail and Frances but retained her Yoruba name- Olufunmilayo.

In 1918, tax policies had been introduced that required women as young as 15, (the age at which they were considered marriageable) including those who were unemployed, to pay three shillings a year as income tax. Men, on the other hand, did not have to pay until they were 18.

She emphasized the need for unity between ‘elite’ women and the market women of the town, for whom she organized night schooling through a ‘ladies club’ that she established. In 1944 the club later expanded to include the market women and, in 1945.

As the ladies’ club became more politicized, it was renamed the Abeokuta Women’s Union (AWU) in 1946. Through this union, Funmilayo organized women in Abeokuta to protest against colonial taxation and other unfavourable policies under the slogan ‘No taxation without representation.’ Taxation was a particularly sore issue for the women of Abeokuta: girls were taxed at 15 and boys at 16, and wives were taxed separately from their husbands, irrespective of their income. The women considered the taxes ‘foreign, unfair and excessive.’

As the leader of the AWU, in the years before Nigeria declared independence from Britain in 1960, Ransome-Kuti often spoke to British district officials to explain her organization’s position – best captured by their slogan “no to taxation without representation”. At the meetings, she would speak in the Yoruba language, leaving officials scrambling for an interpreter.

Ransome-Kuti formed the AWU in 1946 to “defend, protect, preserve and promote the social, economic, cultural and political rights and interests of the women in Egbaland”.

Her aims and objectives were outlined in a document in 1947, called The AWU’s Grievances, one of the sub-headings in which was “Stripped Naked”. It contained a list of wrong-doings by the traditional ruler for “misusing his authority” and by the administration for “not providing medical and educational facilities for women”.

By January 1949, when the pressure became too much for the Alake, he abdicated the throne. The tax on women was abolished whereas the one on men was increased, and four women, including Funmilayo, were named to a new interim council. It had taken the women nearly three years of continuous struggles to win, during which they had remained cohesive, organized, and determined, and had not resorted to violence.

Ademola II, Abeokuta’s new Alake in 1920, was the first to have had a European-style education. He took advantage of his position and British support to forcefully take over lands and imposed taxes that were never accounted for.

Anger mounted again during World War II when the Alake took advantage of colonial orders to increase requisitions. Women were his first targets because they brought chickens, yams, gaari (cassava meal), and rice into the city. All the Alake had to do was set up a few roadblocks to confiscate a large part of the women’s wares, offering the justification that no one should eat as long as the soldiers had not been fed. The women became more impatient, not only with the ill-treatment they endured to make them pay these taxes but also with the fact that, despite the obligations imposed on them, they had neither the right to vote nor any representation -merely the right to complain of having been beaten and bullied.

The women protested against the corruption of the traditional rulers, and their failure to defend the women’s demands or to challenge the colonial authorities. One remarkable event organized by the women’s union was the protest against the Alake, the king of the town, for enforcing food trade regulations that made life uncomfortable for the people. The Egba women of Abeokuta focused their opposition on a local representative of British power rather than on British power itself.

Because the women were unable to get an official permit to gather for demonstration, Funmilayo organized and trained the women for a grand protest which they called a festival.

Thousands of women converged to protest in front of the Alake’s palace and petitioned against the arbitrary taxation. The women were then put on trial as individuals for refusal to pay taxes. Using all means available, the AWU continued its activities and mobilization, with its leaders refusing to pay taxes.

In 1959, Funmilayo was given a sentence of a five-pound fine or three months imprisonment. She refused to pay the fine but still eluded jail. This led to market closures, including using songs to ridicule those in power.

With the dust barely settled on the court case, Funmilayo announced she was going “to stand for election this year and to fight the government of Northern Nigeria into giving the franchise to the women of Northern Nigeria.

‘Communist leanings’

In 1958, the Nigerian government used Ransome-Kuti’s Daily Worker article from more than 10 years earlier, along with trips she had taken to China and the Soviet Union to speak about the plight of Nigerian women, as grounds to refuse to renew her passport. Her “communist leanings” were also opposed by then-Prime Minister of Nigeria, Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

Funmilayo often spoke to British district officials to explain her organization’s position – best captured by their slogan “no to taxation without representation”. At the meetings, she would speak in the Yoruba language, leaving officials scrambling for an interpreter.

Strengthened by its accomplishments, the AWU decided to expand into a trans-regional, trans-ethnic structure and became the Nigerian Women’s Union. Sections were created in many areas, including Kano to the north. Many of its members joined in the struggle for independence with political parties such as the Action Group or the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC). An executive committee was organized to try to keep educated women and often illiterate businesswomen, including several market representatives, on the same footing.

Ransome-Kuti’s political activism led to her membership in the NCNC where she was the only woman to hold an executive position. She was also the only woman to join the Nigerian delegation to London in 1947 to lodge a formal protest with the secretary of state for the colonies.

She would have been labeled an ‘objectionist.’ but it was evident that her objections and struggles were in the interest of the people. Notable among these was her objection to the setting up of the ‘Sole Native Authority’ to the exclusion of the members of the Egba Native Authority. She was an ‘eloquent and compelling speaker’ who efficiently used ‘expressive, idiomatic language and very sharp wit.’ She also extended support to Mrs. Margaret Ekpo, who had commenced an independent resistance to colonial policies in eastern Nigeria.

Increasingly famous for representing women’s interests, Ransome-Kuti was honoured with a doctorate, the Order of the Niger, and the Lenin Peace Prize.

In February 1978, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was thrown out of a window by Nigerian soldiers from the (Kalakuta Republic) home of her son, renowned Afrobeat musician and activist, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Fela was renowned for being critical of military rule by ridiculing them in his songs. Funmilayo died on April 13, 1978, from injuries sustained in the attack on the Kalakuta Republic.

Funmilayo will be remembered as an educator, a feminist trailblazer, and a political activist whose fierceness earned her the title of ‘Lioness of Lisabi’.

Kindly like, comment, follow, and share.